Punishing the Past, Preserving the Present: Pakistan’s Accountability Paradox

A historic sentence raises enduring questions about power, control, and selective institutional accountability

The sentencing of a former senior intelligence official to 14 years of imprisonment marks an uncommon moment in Pakistan’s civil–military history. Observers familiar with the December developments note that convictions of this level are rare and often framed as watershed moments. Yet historical patterns suggest caution. Accountability actions within the military domain have frequently been selective, designed to isolate individual figures while leaving broader institutional practices intact.

What makes this episode significant is not only the severity of the sentence but the explicit acknowledgment—through official communication—that political interference, misuse of authority, and violations of secrecy laws were part of the charges. This acknowledgment moves beyond vague references to “discipline” and places political activity squarely within the scope of punishable conduct. The question is whether this represents a genuine shift toward systemic accountability or a controlled intervention aimed at managing public pressure.

More: Behind the Optics: What the Faiz Hameed Verdict Reveals About Pakistan’s Power Struggle

Law, Process, and the Boundaries of Transparency

According to journalists covering the civil–military situation, the legal process followed established military procedures, including the right to counsel and avenues for appeal. From a formal legal standpoint, this satisfies procedural requirements. However, transparency remains limited. Court-martial proceedings are not public, evidence is not disclosed, and findings are communicated through brief institutional statements rather than detailed judgments.

This opacity creates a credibility gap. While the sentence signals enforcement, the absence of publicly verifiable detail restricts independent assessment of proportionality, consistency, and precedent. At the same time, political supporters and legal observers point to a broader pattern surrounding the detention of former prime minister Imran Khan, noting that more than 200 political cases have been filed against him. They argue that these cases are intended to break his political resistance to military involvement in democratic processes, to use the political parties associated with the Sharif and Zardari families as instruments of governance, and to keep him incarcerated for an extended period. According to these accounts, offers of release in exchange for prolonged political silence were made on multiple occasions and were reportedly declined by Imran Khan. They further contend that expedited late-night court proceedings, followed by lengthy adjournments, have been used to prolong legal uncertainty, allowing the current political arrangement to remain intact. In democratic systems, accountability derives not only from punishment but from visibility—allowing society to understand how decisions were made and whether standards will apply uniformly in the future. Critics also argue that following the 27th constitutional amendment, the judicial order itself has been severely undermined.

Individual Guilt Versus Institutional Conduct

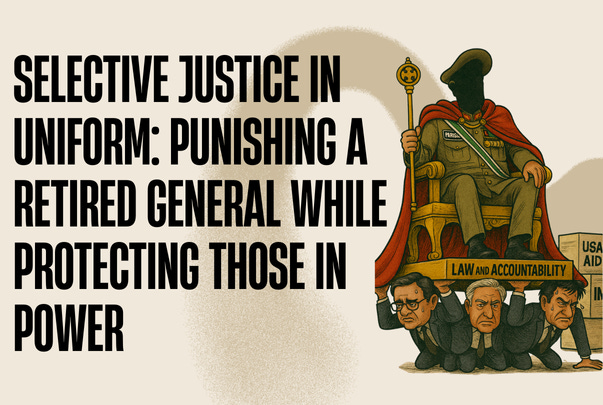

Independent political analysts argue that the case of former ISI chief General Faiz Hameed exposes a deeper structural flaw in Pakistan’s civil–military framework. Large-scale political interference cannot be executed by a single officer acting in isolation; it requires a functioning chain of command and coordination across intelligence agencies and institutional actors. Activities such as intelligence operations, electoral management, and information control are inherently collective processes within the military establishment’s political role. Viewed in this context, assigning accountability to one retired general raises serious questions about how responsibility is defined and distributed across the wider military and intelligence system

The sentencing of former ISI chief General Faiz Hameed represents an unprecedented moment in Pakistan’s military history. For the first time, a senior intelligence chief has been formally convicted for political interference—something that was never pursued against past military rulers or dictators. However, this very novelty sharpens the underlying question raised by analysts: while the punishment establishes an important precedent, it also isolates accountability at the level of a single retired officer. Given the hierarchical and coordinated nature of intelligence operations and political management, the case inevitably invites scrutiny over whether responsibility is being narrowly defined, rather than examined across the wider command structures and institutional mechanisms through which such actions are typically executed.